|

| Bio |

| Resume |

| Exhibits |

| Publications |

| Media |

|

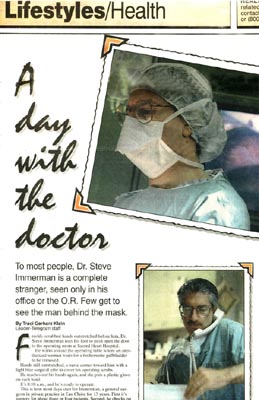

"A Day with the Doctor"Published in the Eau Claire Leader-Telegram Wednesday, April 5, 1995 |

| To most people, Dr. Steve Immerman is a complete stranger, seen only in his office or the O.R. Few get to see the man behind the mask. Freshly scrubbed hands outstretched before him, Dr. Steve Immerman uses his foot to push open the door to the operating room at Sacred Heart Hospital. He walks around the operating table where an anesthetized woman waits for a bothersome gallbladder to be removed. Hands still outstretched, a nurse comes toward him with a light blue surgical robe to cover his operating scrubs. He reaches out his hands again, and she puts a plastic glove on each hand. It's 8:10 a.m., and he's ready to operate. This is how most days start for Immerman, a general surgeon in private practice in Eau Claire for 13 years. First it's surgery for about three or four patients. Second, he checks on postsurgery patients on the seventh floor. Third, he grabs lunch and heads to his office at 719 W. Hamilton Ave. to see patients. On Mondays and Fridays his schedule is open to operate all day. On this recent morning he'll do three surgeries - this gallbladder, a partial mastectomy and a breast biopsy. He's also got me tagging along. I'm participating in a State Medical Society mini-internship, along with about 20 other people in the community, to see what it's like to be a doctor. Immerman walks over to the patient. Also in the room are a circulating nurse, who makes sure all the necessary equipment is in its place and things move smoothly, a nurse anesthetist, who monitors the patient's vital signs, and two surgical technicians, one who hands Immerman surgical instruments and another who helps him hold instruments in the patient's abdomen as he operates. An anesthesiologist also moves in and out of this operating room and others to check on patients. The room is fairly quiet as the surgery begins, except for the voices of the Supremes singing "Stop in the Name of Love" on the radio. A technician hands Immerman a No. 15 scalpel, which he uses to make a few incisions in various spots on the abdomen. After the first incision, the patient's stomach is filled with carbon dioxide so the abdominal wall is away from the organs. This is called laparoscopic surgery. Immerman then inserts a telescope-like instrument, which allows him to watch his work on two television screens on either side of the operating table. In the other small incisions he inserts an instrument to hold the scope in place and his tools to help him remove the gallbladder, which contains a large gall stone. "I'll make the standard 1-centimeter incision, but it's a 2 centimeter stone," he told me as he vigorously scrubbed his hands and arms with soap a few moments before entering the room. "I"ll either have to break it or make the hole larger," he said. Cuts made and tools in place, he's in the abdomen with the tiny scope in just a few minutes. He points to the TV directly across from him, which shows a clear picture of the inside of the woman's abdomen. "One problem with laparoscopy is there is no sense of touch and we don't have a three dimensional view," Immerman tells me. "But it's a very good picture." "We had the tactile sense," he says of the days before laparoscopy when every patient was opened up for surgery. "But we couldn't see this kind of detail." He's pointing out the main bile duct and an artery, which are important to identify and not cut, be says. Even though he thinks he's found them, he continues to probe For a few minutes. "You want to make completely sure you've found them," he says. He's sure, so he inserts an electrical cautery tool into one of the incisions. It uses heat to separate he gallbladder from the liver's surface and seals off the blood vessels. Immerman points out the temporary smoke the tool causes in the abdomen. "There, now it's off and we just need to remove it," he says as he moves the gallbladder toward the incision. "Yeah, it's a little bigger than I thought," he says, looking at the TV screen. As predicted, he makes the incision a bit bigger and pulls the gallbladder through, dispensing it into sterile silver cup. The woman's abdomen is cleaned out with a saline solution and checked for bleeding. The gas is let out, and Immerman stitches her up. It's 8:45 a.m., and Immerman takes off his gloves and robe and leaves the room. He heads down he hallway to the recovery room, where his patient will show up a few minutes later. He sits down at a computer, where he calls up his file for laparoscopy and adds a few notes for this particular patient. She will receive a printout of his instructions for recovery. Next he picks up a phone, dials a number and begins dictating the surgery. He talks fast, hesitating rarely. I'm amazed the medical transcriptionists, who type up dictations, can understand his speedy talk. "They put it on slow," he says, laughing. He heads down the hall to the waiting room to talk to the woman's family members, who are happy to hear everything went well. "When things go well, you forget it," Immerman says as we head back to the surgery area. "When things go bad, you never forget it." He tells me about the next patient, an 80-year-old woman who had a tiny area of cancer on her breast removed. "When we removed it initially we weren't sure if we got it all," he says. "We're going back to get clear of it." Her options were to do a partial mastectomy and radiation, or a mastectomy and no radiation. The woman chose the partial mastectomy, also known as a lumpectomy. Sometimes with older patients, the decision whether or not to proceed with full treatment can be more complicated, Immerman says. "She didn't want to compromise, and nobody gives me the right to say she shouldn't get the full treatment if that's her choice," he says."I have a certain respect for people that age who choose to get the treatment." Still, he does tell patients if he thinks they will have a difficult time handling treatments. About a half-hour after the first surgery, Immerman's back in the same operating room to do the lumpectomy. Like the patient before, this woman is under general anesthesia, and Immerman goes through the same routine - scrub up, put fresh robe and gloves on. In blue marker, he draws a crescent shape on the woman's breast and begins to cut along the line. "We're taking out a generous area,"he tells me. When the cut is complete, he uses the cautery tool to burn away the breast tissue. "Cautery gives a clean cut and minimizes the bleeding," Immerman says as he works. "It also saves time. If I did it with a knife, everything would be bleeding and I'd have to spend time stopping the bleeding," Immerman says as he works. |

Within several minutes the area is removed, and Immerman carefully stitches it closed. |